To Be Fair by Mohamed Somji

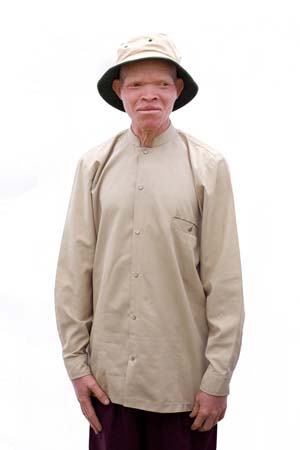

To be Fair, a photography project by Mohamed Somji focuses on the albino population - and a very marginalised community - in Tanzania, a very marginilised communty . I first saw this series in May at Gulf Photo Plus' Slidefest. I was quite moved by this series of portraits and I hope you like it too.

Here are Mohamed's thoughts (in his own words) about this series.

In Tanzania, a group of children play soccer in a field. The sun reaches its afternoon apex, and, before long, one boy retreats from the game. His light pink skin and pale hair starkly distinguish him from the others. Squinting, he seeks protection under a shady tree. He’s an albino, and his impaired skin pigmentation makes him extremely sensitive to the light. Along with other Tanzanian albinos, his lifestyle is normal by most respects; he just needs to be careful. Not only of the sun, but also of prevailing misconceptions, discrimination, and, in the last several years, superstitions that put a high price on his blood.

Albinism is a rare genetic disorder inhibits melanin in the skin, eyes and hair. It affects an international minority, but confers severe liabilities in equatorial Africa, where dark complexions are the majority, the sun is relentless, and prejudices are strong. Albinos have long wrestled with sub-Saharan stigmas and environmental pressures, but Tanzanian albinos contend with a particularly difficult hurdle. Local superstitions preach that albinos have inherent magic, the power of which can be dispersed through their hair, bones, and skin. The belief was put into practice, and harvested body parts have been distributed to witch doctors as far as Congo; albino hair woven in fishing nets for a bountiful catch.

Inexorably embedded in the continent’s history, the sacrifices have been going on for as long as albinos have been in Africa. In 2007 the killings increased, particularly in Tanzania. Evasive villages couldn’t bury the tallies. The mutilations were chilling and brutal, and the media reacted accordingly. Photographs and interviews offered stark portraits of albinos, and grave accounts of the assaults. And the international attention was effective. It yielded local NGOs with sunscreen and medical aid, and legislation that curbed the black market. Several traders have been prosecuted; one has been executed. In 2008, a woman was named as the first albino Member of Parliament. Tanzania's progress has not been insignificant, but, four years later, the systemic marginalization of albinos persist, and so do the killings.

Demonized or prized, albinos have always been exoticized. Physical differences are seen as abnormalities, a perception that eclipses their identity as Tanzanians, with the rights and realities afforded therein. Tanzania's education is thin, and its rural culture is broad. Local fears become hegemonic beliefs, and any shift must happen from within. So while the international media established the violent discrimination as a human rights issue, other approaches are needed to effect how they are perceived in their country. This essay is an attempt to do so, by replacing sympathy or intrigue, with energy and equality.

Photographed in a street studio under a cloth and the sun, the twenty-five albino portraits in Dar-es-salaam and Arusha could be taken anywhere. Excluding a signifying environment and its legacies, they hope to move history forward, and Tanzania’s people beyond its fearful past. The essay focuses on its subjects with inspired immediacy, showing Tanzanian albinos as happy and ordinary. Rather than specimens, they’re mothers, brothers, friends, ordinary people. They’re always aware of their particular challenges — physical and cultural — which is to say their victories are not unique: scoring a goal, finishing a long book, finding a community, falling in love.

They contend and they celebrate, not unlike anyone else.